Since it was discovered that the Zika virus has been transmitted by local mosquitoes in Miami, Florida, many people across the country have become increasingly concerned about getting bitten by a mosquito.

But Missourians need not worry for now as probability of contracting Zika from mosquitoes in the state are low, according to Dr. David Claborn, Missouri State University associate professor of public health.

Surveying mosquitoes

As part of a contract from the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS), Claborn and his team of researchers have traveled across the southern part of the state since June, trapping mosquitoes at parks and wrecking yards, and studying them to see if any are Aedes aegypti (also known as the Yellow Fever mosquito), which is the primary vector of Zika.

A vector is an organism that spreads infections by transmitting bacteria or virus from one host to another.

The team completed the fifth and final Missouri River route for this year on Sept. 22. It stretched from Springfield to Jefferson City to Columbia.

“We’ve trapped about 15,000 mosquitoes overall and have not found any specimens of the primary vector,” said Claborn. “This does not mean it does not occur in Missouri; however, if it does occur, the population is not large or easy to detect.”

Claborn added they have found a healthy population of a secondary vector, Aedes albopictus (also known as the Asian Tiger mosquito) but it’s presently not known how well this type of mosquito can transmit Zika in a temperate environment such as in Missouri.

The trap

The process of trapping mosquitoes involves using a variety of adult traps with an attractant such as carbon dioxide next to a fan. The fan catches the flying mosquito and forces it into a collection bag.

“Perhaps more useful is the larval collection, which is done with a standard mosquito dipper or in smaller habitats such as a tire, with a turkey baster. The larvae are returned to the lab where they are reared to the adult stage to facilitate identification,” Claborn said.

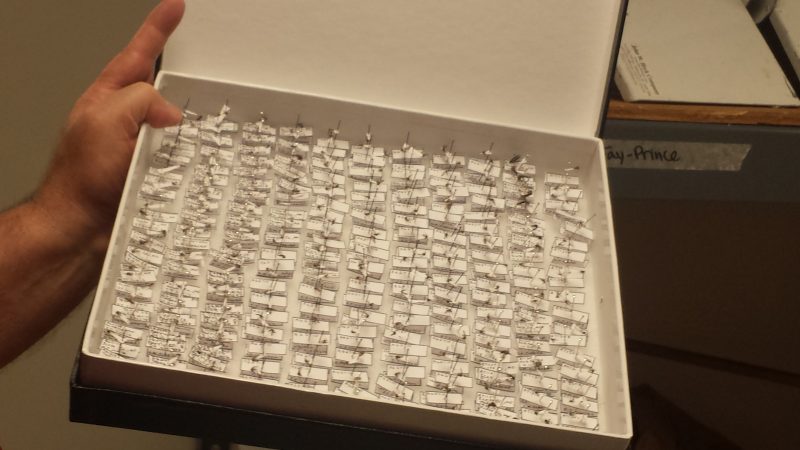

After the identification process is completed, the mosquitoes are labeled according to species and location of collection, given a unique number that corresponds to a GPS site and placed in sample boxes.

“What we wanted to know from this research is what mosquitoes are here and in what numbers they occur because some of them can serve as transmitters of the virus,” said Claborn.

The information resulting from this research project is passed on to DHSS who, in turn, shares it with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Other members of the research team included Dr. Kip Thompson, Missouri State assistant professor of public health; Dr. Dalen Duitsman, director of Ozarks Public Health Institute; and two public health graduate students, Madison Poiry and Daniel Famutimi.

For more information, contact Claborn at 417-836-8945.