The human body is an amazing thing. As you form, the cells in your body talk to each other to decide who gets to be a heart cell and who gets to be part of the brain, skin, liver—The list goes on and on. Eventually, you form into the person you are today.

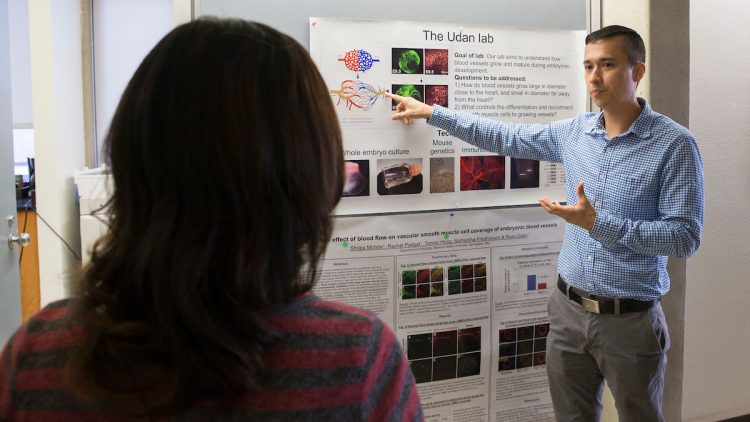

That’s the reason Dr. Ryan Udan, assistant professor of biology at Missouri State University, became interested in developmental biology.

“What fascinated me the most with this field is learning every single process that must occur for a person to be made,” said Udan.

The wonder of the human body, of cells communicating with each other, sparked his new heart research.

Learning about the heart

February is American Heart Month. It’s a time to study the organ that needs to be healthy for survival.

How the cardiovascular system forms in utero is a mystery. This makes it hard to determine why hearts don’t always form perfectly.

Each year, one percent (about 40,000) of babies in the United States are born with congenital heart defects (CHDs). This means doctors need to fix the heart before it can do its job properly.

Right now, doctors have to wait until the baby is born to fix these defects, which include holes in the tissue that separates the heart chambers, hearts that are too big or too small or blood vessels that are improperly connected with the heart or each other.

“We hope that by discovering the root cause of these defects, this may lead to the development of therapeutic interventions to improve or potentially cure these defects during embryonic or fetal development,” said Udan.

How blood flow partners with the heart

It’s already known that CHDs can happen because of genetic mutations or by environmental factors, such as drugs or chemicals. One new discovery Udan made is how blood flow factors into heart development.

The heart is responsible for pumping blood to the rest of the body. It makes sure blood is oxygenated and nutrient rich.

However, during the development of the heart, it’s the other way around. When the heart doesn’t get enough blood flow during development, it shrinks. The heart is smaller, and the heart wall is thinner than it should be, resulting in a CHD.

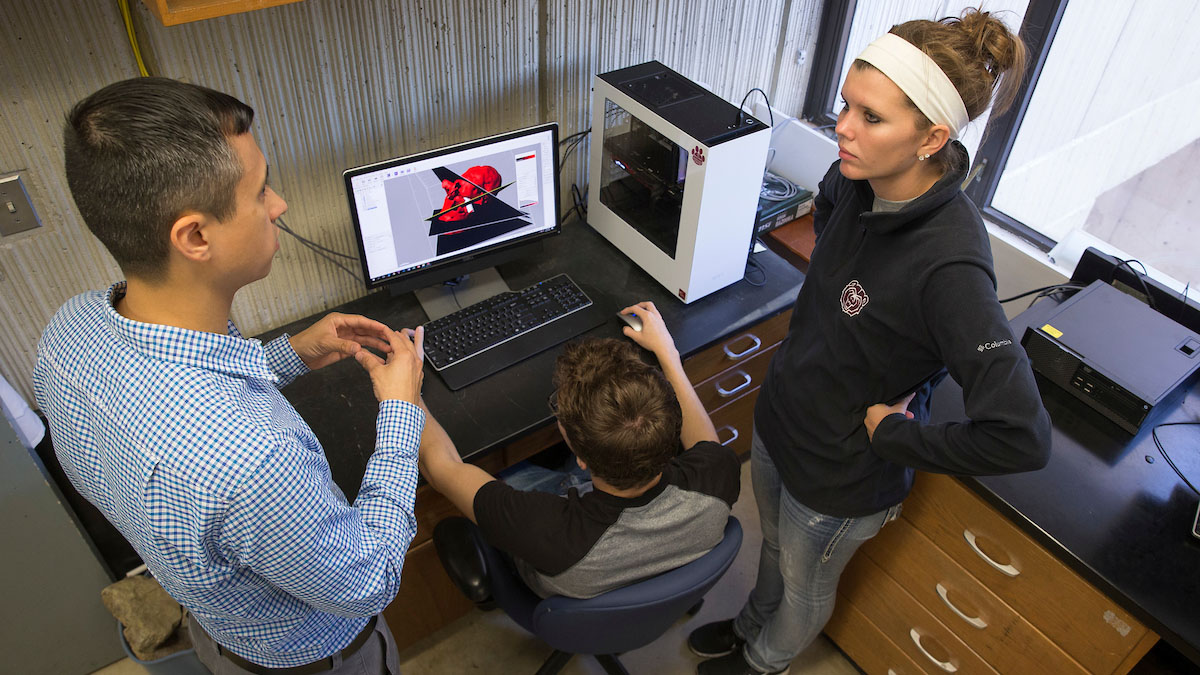

Former MSU master’s student Samantha Frederickson and current MSU master’s student Tanner Hoog, both advised by Udan, visited Baylor College of Medicine. They made 3D images to analyze heart development in experimental and healthy mouse embryos using an optical projection tomography (OPT) microscope. There are only a few OPT microscopes available to use in the United States.

These images allowed them to measure the kinds of structural changes that occur in the developing heart upon manipulation of blood flow.

“We are learning more that if the developing heart doesn’t function properly, causing abnormal blood flow, this can cause a positive feedback loop that exacerbates the condition,” said Udan.

This means that if the heart starts out with a slight issue, over time the condition will worsen.

Knowing this, Udan can now work on a solution for poor blood flow in a developing heart.

“Blood flow has a very critical role in cardiovascular development,” said Udan.