When no written history for a region exists, local folklore and fables have the potential to dominate the understanding of its past.

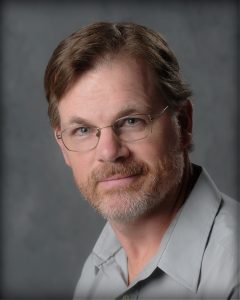

“There’s so much misunderstanding about the Ozarks, whether it’s the hillbilly stereotype or the isolated frontier myth,” said Dr. Brooks Blevins, professor of Ozarks studies at Missouri State University. “What I’ve tried to do is write a comprehensive history of the Ozarks in the hopes of dispelling as many of those misunderstandings as I possibly can.”

By compiling stories from letters, diaries and published histories from Missouri, Arkansas and Oklahoma, Blevins is working to shed new light on the rich history of the Ozarks.

To date, Blevins’ research has produced two complete book manuscripts. His first book begins with the Native American days of the Osage and the Cherokee and chronicles the Ozarks all the way up to the Civil War era, which is the second book’s primary focus.

Geographical vs. cultural boundaries

Before Blevins, no one had ever attempted to write a comprehensive history of the Ozarks. To do the job properly, according to Blevins, it’s important to understand that the physical boundaries of the Ozarks are not the same as its cultural boundaries.

“For the first book, I used the geographer’s standard definition of the Ozarks, which outlines the region using the Missouri, Arkansas and Mississippi rivers,” said Blevins. “By the time you get to the second book, however, you’re talking about the cultural Ozarks.”

The cultural boundaries of the Ozarks are not as clearly defined as its physical borders. Towns like Ste. Genevieve on the Missouri/Illinois border, while technically in the physical Ozarks, do not fit into the cultural Ozarks. Some areas of the map shrink, while other sections grow.

As a region of the United States that has long been associated with the hillbilly stereotype, cultural identification with the Ozarks has the potential to evoke strong reactions.

“The cultural Ozarks is going to be basically the part of the country where people identify themselves as living in the Ozarks,” said Blevins. “There are places that geographers call the Ozarks where the people who live there would pass out if you called them an Ozarker — culturally, they just don’t identify with the Ozarks.”

Settling the Ozarks: Myths of the frontier

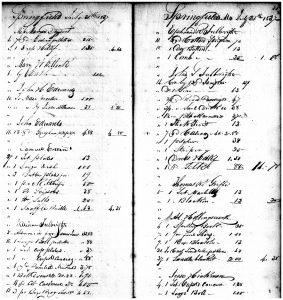

While European settlers began to trickle into the area as early as the mid-1700s, widespread migration to the Ozarks didn’t occur until after the War of 1812. These early settlers, according to Blevins, lived much differently than cultural myths might lead one to believe.

“The average person probably assumes that people in the Ozarks lived isolated, frontier lives: a hand-to-mouth existence where they weren’t connected to the broader currents of American economics, life and culture,” said Blevins. “But it usually didn’t happen that way — there was more community and contact with the outside world than we are led to believe.”

While they still might have made their money through agriculture, trapping and hunting, 19th century residents of the Ozarks were actually quite active in their communities and the political structure of the time.

“It’s one of those ongoing stereotypes that we in the Ozarks often buy into willingly,” said Blevins. “It can seem romantic to think of these people who were living 10 miles from their nearest neighbor and getting by on living in a little log cabin and barely making ends meet. What I found is that most of them were actually very connected. In those days, they were on the edge of the civilized United States.”